PNAS|Flying, nectar-loaded honey bees conserve water and improve heat tolerance by reducing wingbeat frequency and metabolic heat production

Significance

Despite the need to be able to predict the effects of climatic warming on animals, we lack methods to assess actual thermal limits of flying insects, such as pollinators. We assessed the relative danger of overheating and desiccation for honey bees carrying loads. Due to the capacity of hot bees to reduce metabolic heat production during flight, our data suggest that under dry and poor forage conditions, desiccation may limit activity before overheating, impairing critical pollination services provided by honey bees.

Abstract

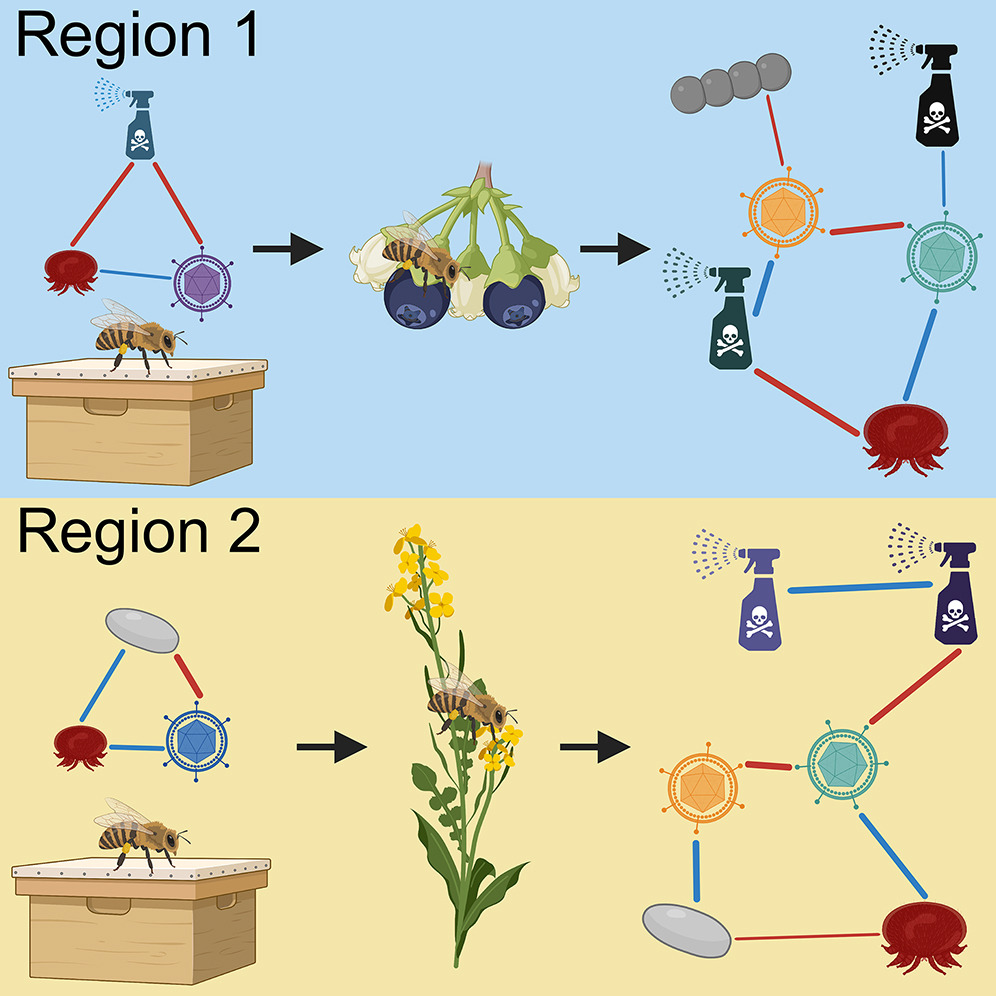

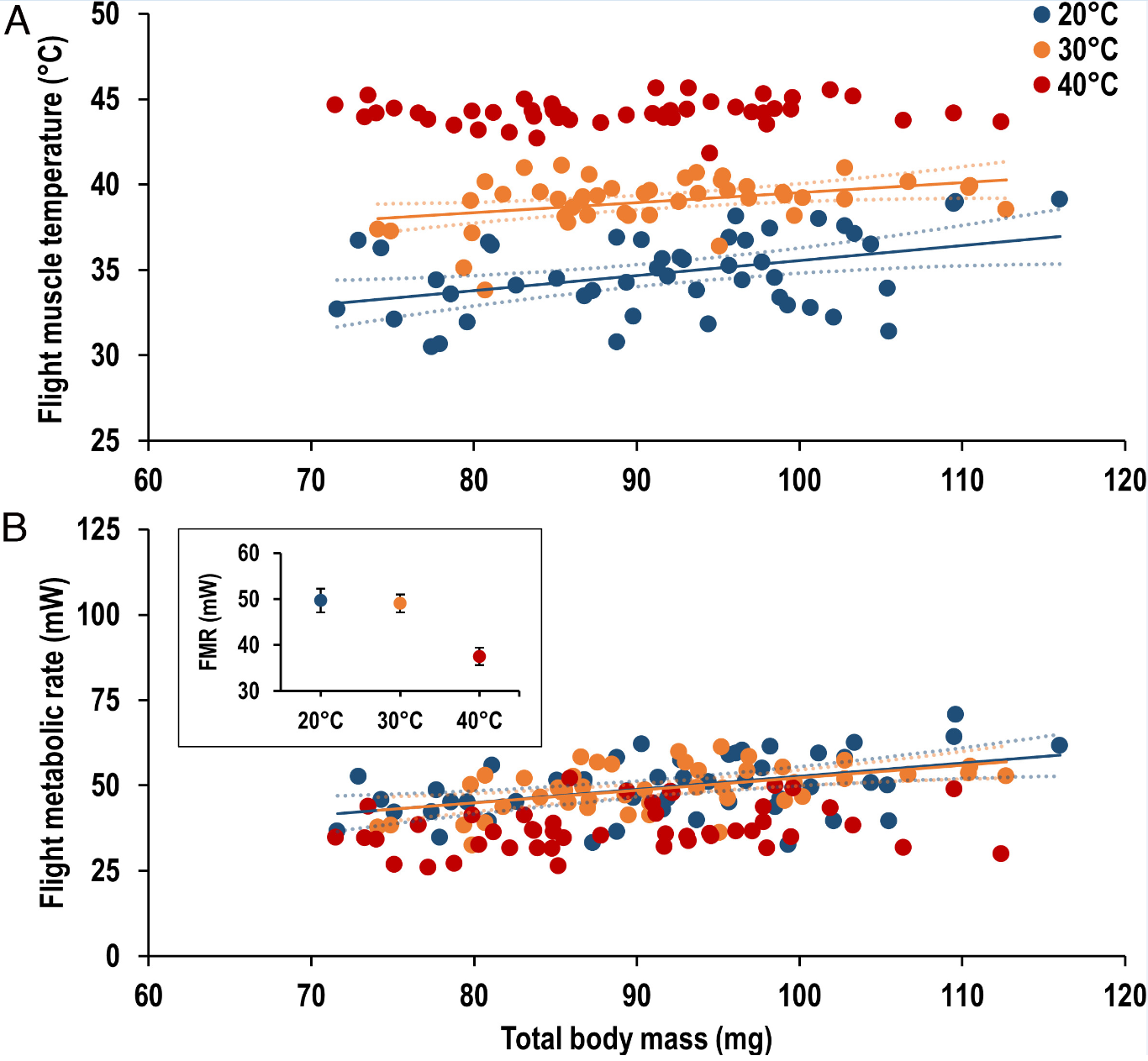

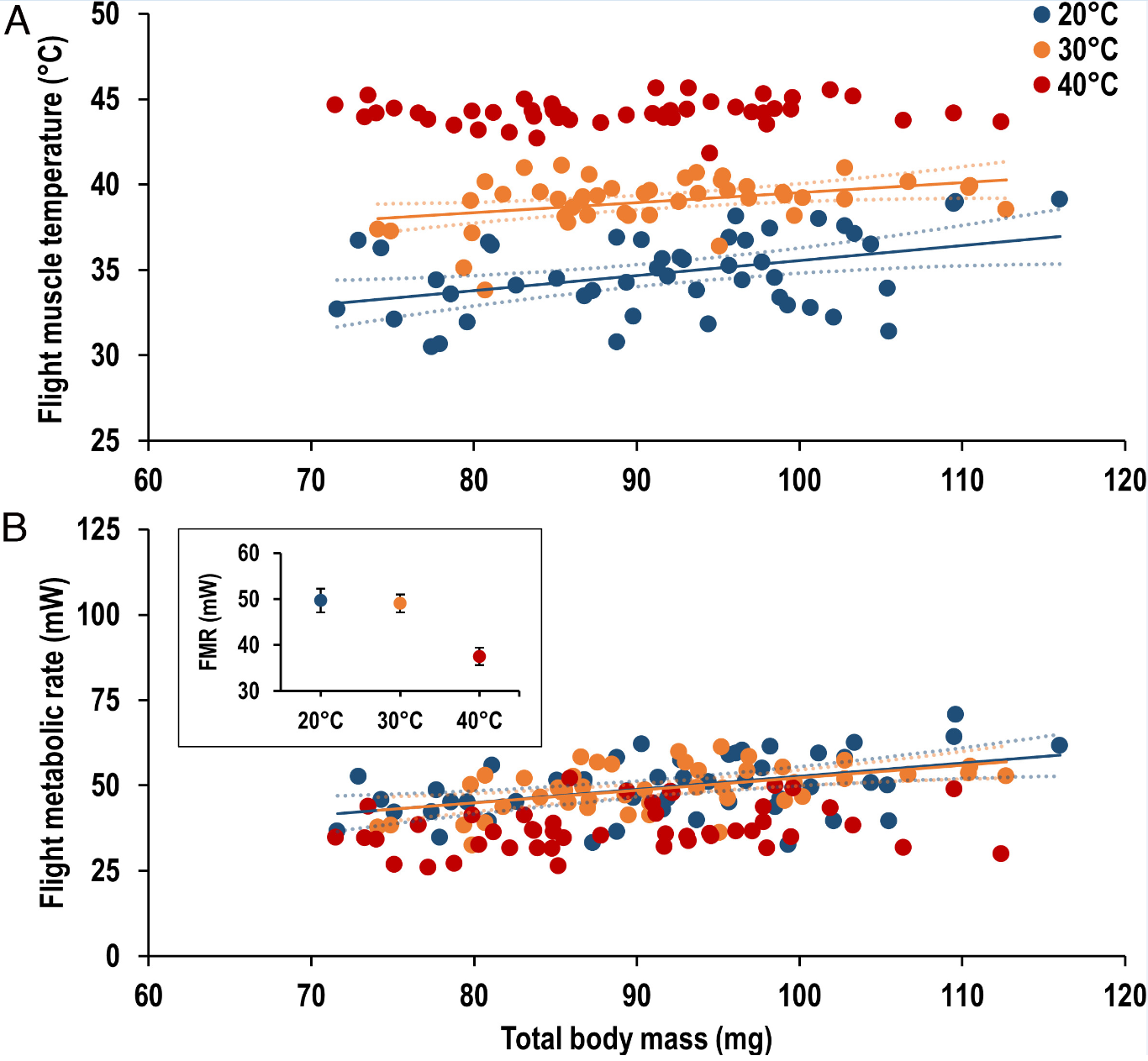

Heat waves are becoming increasingly common due to climate change, making it crucial to identify and understand the capacities for insect pollinators, such as honey bees, to avoid overheating. We examined the effects of hot, dry air temperatures on the physiological and behavioral mechanisms that honey bees use to fly when carrying nectar loads, to assess how foraging is limited by overheating or desiccation. We found that flight muscle temperatures increased linearly with load mass at air temperatures of 20 or 30 °C, but, remarkably, there was no change with increasing nectar loads at an air temperature of 40 °C. Flying, nectar-loaded bees were able to avoid overheating at 40 °C by reducing their flight metabolic rates and increasing evaporative cooling. At high body temperatures, bees apparently increase flight efficiency by lowering their wingbeat frequency and increasing stroke amplitude to compensate, reducing the need for evaporative cooling. However, even with reductions in metabolic heat production, desiccation likely limits foraging at temperatures well below bees’ critical thermal maxima in hot, dry conditions.

|