The combined impacts of pesticides and air pollution on bees could have severe consequences.

Whether it’s exhaust fumes from cars or smoke from power plants, air pollution is an often invisible threat that is a leading cause of death worldwide.

Breathing air laced with heavy metals, nitrogen oxides and fine particulate matter has been linked to a range of chronic health conditions, including lung problems, heart disease, stroke and cancer.

If air pollution can harm human health in so many different ways, it makes sense that other animals suffer from it too. Airborne pollutants affect all kinds of life, even insects.

Health

In highly polluted areas of Serbia, for instance, researchers found pollutants lingering on the bodies of European honeybees. Car exhaust fumes are known to interrupt the scent cues that attract and guide bees towards flowers, while also interfering with their ability to remember scents.

Now, air pollution may be depleting the health of honey bees in the wild, a new study from India has revealed. These effects may not kill bees outright. But like humans repeatedly going to work under heavy stress or while feeling unwell, the researchers found that air pollution made bees sluggish in their daily activities and could be shortening their lives.

India is one of the world’s largest producers of fruit and vegetables. Essential to that success are pollinator species like the giant Asian honey bee. Unlike the managed European honey bee, these bees are predominantly wild and regularly resist humans and other animals eager to harvest their honey. Colonies can migrate over hundreds of kilometres within a year, pollinating a vast range of wild plants and crops across India.

Researchers studied how this species was faring in the southern Indian city of Bangalore, where air pollution records have been reported as some of the highest in the country. The giant Asian honey bees were observed and collected across four sites in the city over three years. Each had different standards of air pollution.

The number of bees visiting flowers was significantly lower in the most polluted sites, possibly reducing how much plants in these places were pollinated. Bees from these sites died faster after capture, and, like houses in a dirty city, were partly covered in traces of arsenic and lead. They had arrhythmic heartbeats, fewer immune cells, and were more likely to show signs of stress.

Pollination

There are some caveats to consider, though. For one thing, areas with high pollution might have had fewer flowering plants, meaning bees were less likely to seek them out.

Also, the researchers looked at the health of honey bees in parts of the city purely based on different levels of measured pollution. They couldn’t isolate the effect of the pollution with absolute certainty – there may have been hidden factors behind the unhealthy bees they uncovered.

But, crucially, it wasn’t just bees that showed this trend. In a follow-up experiment, the study’s authors placed cages of fruit flies at the same sites. Just like the bees, the flies became coated in pollutants, died quicker where there was more air pollution, and showed higher levels of stress.

The threat posed by pesticides is well known. But if air pollution is also affecting the health of a range of pollinating insects, what does that mean for ecosystems and food production?

Our diets would be severely limited if insects like honey bees were impaired in their pollinating duties, but the threat to entire ecosystems of losing these species is even more grave. Crop plants account for less than 0.1 percent of all flowering species, yet 85 percent of flowering plants are pollinated by bees and other species.

Solutions

Giant Asian honey bees like the ones in Bangalore form large, aggressive colonies that can move between urban, farmed and forest habitats. These journeys expose them to very different levels of pollution, but the colonies of most other types of wild bee species are stationary.

They nest in soil, undergrowth or masonry, and individuals travel relatively short distances. The levels of pollution they’re regularly exposed to are unlikely to change very much from one day to the next, and it’s these species that are likely to suffer most if they live in towns or cities where local pollution is high.

Thankfully, there are ways to fix this problem. Replacing cars with clean alternatives like electrified public transport would go a long way to reducing pollution. Creating more urban green spaces with lots of trees and other plants would help filter the air too, while providing new food sources and habitat for bees.

In many parts of the UK, roadside verges have been converted to wildflower meadows in recent years. In doing so, are local authorities inadvertently attracting bees to areas we know may be harmful? We don’t know, but it’s worth pondering.

Exposure

From September 2020, Coventry University is launching a citizen science project with the nation’s beekeepers to map the presence of fine particulate matter in the air around colonies, to begin to unravel what’s happening to honey bees in the UK.

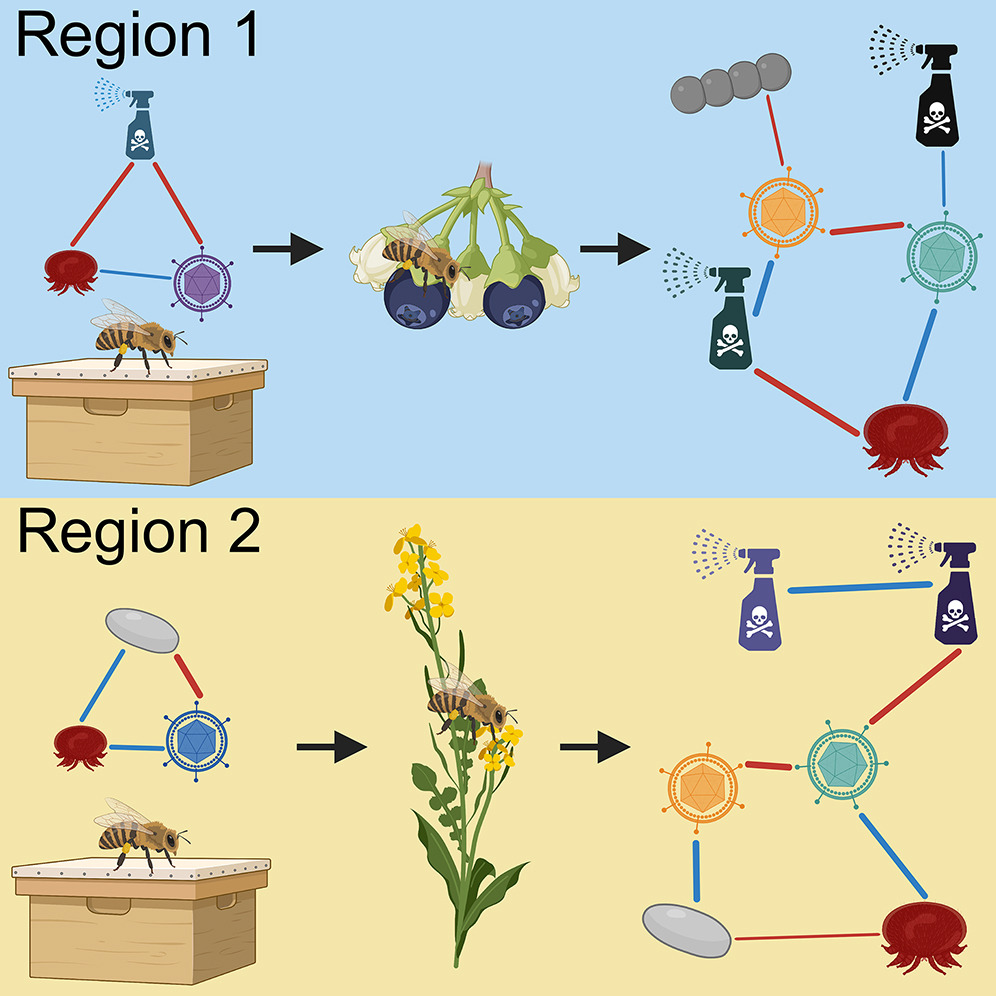

Air pollution is likely to be one part of a complex problem. Bees are sensitive to lots of toxins, but how these interact in the wild is fiendishly difficult to disentangle.

We know cocktails of pesticides can cause real damage too. But what happens when bees are exposed to these at the same time as air pollution? We don’t yet know, but answers are urgently needed.

These Authors

Barbara Smith is associate professor of ecology at Coventry University. Mark Brown is professor of evolutionary ecology & conservation at Royal Holloway. This article was first published on The Conversation.

|